The Most Famous Ukiyo-e Japanese Woodblock Art Prints

Japanese woodblock art printmaking or Ukiyo-e, “Art of The Floating World” from the Edo Period (1603 – 1868) were hugely popular and influential not only for local Japanese culture, but for westerns alike.

Ukiyo-e of Japan

For most westerners Andy Warhol commands the title as the first commercializer of art, with his Campbell’s soup cans and mass production of prints. However, as is typical of most “firsts” which are stolen by the west, true mass production of art printing was thriving in the east, specifically Edo, Japan as early as the 1600 CE in the form of Ukiyo-e, or woodblock art prints.

Where Warhol constitutes a household name today, in Edo of the 17th-19th centuries, household names included Hiroshige, Hokusai and Kunichika, among others. Their widely produced Ukiyo-e established them as well known stars, similar to famous kabuki actors, war heroes, and teahouse beauties.

FIVE main categories of Ukiyo-e Art Prints

During the Edo period there were five main categories of woodblock art prints: beauties, landscapes, warriors/heroes, actors and shunga (illegal, sexually explicit). Of these, the more widely known in the world now are by far the landscape series, especially the “36 Views of Mount Fuji” by Utagawa Hiroshige and separately, the series with the same name by Katsushika Hokusai, of which includes the infamous “Under The Great Wave of Kanagawa”.

Ten FAMOUS Ukiyo-e Japanese Woodblock Art Prints

1. Under The Great Wave of Kanagawa

Katsushika Hokusai, c. 1830 ōban (ōban refers to the standard “large size” print form of the Edo period Ukiyo-e woodblock prints).

By far the most well known Edo print of all time, “The Great Wave” as it is commonly known, comes from Hokusai’s series titled 36 Views of Mount Fuji. This print was widely celebrated and collected during its time by European and French collectors especially and has been copied and reproduced considerably over the centuries.

2. The Plum Garden at Kameido Shrine

Utagawa Hiroshige, c. 1857 ōban (“large size print format”).

This print comes from Hiroshige’s series One hundred views of famous places in Edo. Van Gogh copied this design in 1887 and in doing so solidified it in history as one of the great influential art prints from Ukiyo-e Art. The tree featured is known as the “Sleeping Dragon Plum” and was lauded for its purity in double white blossoms, known in the time to be so white they could drive out the darkness of the soul.

Utagawa Hiroshige, c. late 1830’s, ōban (“large size print format”).

Of Hiroshige’s three most famous series, this print comes from his last titled One hundred views of famous places in Edo. Hiroshige, best known for his wide, sweeping landscapes, finished this print to complete the Kisokaidō highway series abandoned by his contemporary Ukiyo-e artist Keisai Eisen. Many of Hiroshige’s best loved designs feature people going about familiar tasks tied to the seasons, nature and rituals.

4. Tako to Ama, The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife

Katsushika Hokusai, Part of a three-volume shunga erotica book (“Young Pines”), published 1814.

This print falls in the illegal art category (shunga, or erotic art) and is important to include as it is to date one of the most well known representations of Japanese Edo art as well as classical shunga. Further, this fascinating image of a classic Japanese myth, “The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife”, reveals how artists under the Tokugawa shogunate, who restricted sexual imagery, creatively depicted intercourse and sexual acts without breaking the law. Artists were thus able to offer this eroticism to their viewers without much recourse to explicit imagery. Shocking though it may seem to our western eyes, at the time this would have been a common, beautiful image of shunga and was widely distributed among print collectors and normal everyday households.

5. The Teahouse Waitress Takashima Ohisa

Katsukawa Shunchō, ōban, c. 1790’s.

Second only in popularity to prints of kabuki actors, prints of desired beauties of the time featured the latest fashions and hairstyle as well as subdued eroticism, which further enhanced their appeal to popular audiences. Shunchō represents a famed beauty who was is rendered coyly covering her face with an elegant fan which bares her personal crest, the three oak leaves. Her splendid garments and summery air would have made this print especially beautiful and desirable for the season. The background shimmers with mica, a mineral powder commonly used in woodblock printing to brighten and shimmer paint.

6. The Actor Otani Oniji III as Edobei in the Kabuki Play Koi nyobo somewake tazuna (The Beloved Wife's Particolored Reins)

Tōshūsai Sharaku, c. 1794

By far the most popular prints of the time, Kabuki actors were displayed in all their grotesque and dramatic glory with bright, contrasting colors, complicated action scenes and striking facial expressions. Kabuki theatre was and still is a unique and integral part of Japanese artistic culture. In Kabuki, actors (played by all men) depict roles with a variety of stylized often overly dramatic expressions and costumes, accompanied by traditional music, long frozen holds and various theatre nuances such as the grand introduction - a specific trope where the main actor lauds himself personally along with his fans in front of the frozen actors on stage. Each famous actor of the Kabuki stage became a legend in their own right, and the artists of the time did well to represent each actor’s individualistic style in their prints even underneath the roles which they often played.

7. The Sea at Satta in Suruya Province

Uttagawa Hiroshige, from the series Thirty-six views of Mount Fuji, c. 1859, ōban.

One of three major landscape series by Hiroshige, this landscape print pays homage to Hokusai’s The Great Wave in its striking upward movement and dramatic, deeply curved waves. All landscape prints represent a late development in the designs of Ukiyo-e; before the 1830’s, the main focus of print designs were beauties, actors and urban life. Landscape prints which became popular after the 1830’s signify a change in the artist’s eye for drawing more complex perspective as well as a shift to more artistic, nature focused, intrinsically beautiful print designs of landscapes. This shift could suggest a rise in leisure travel within Japan and thus demand for souvenirs of well visited places, such as Mount Fuji.

8. Evening Glow at Ryōgoku Bridge

Torii Kiyonaga, from the series Eight Views of Edo, c. 1782, chūban.

This specific style of landscape print utilized by Kiyonaga, where the viewer seems to be looking through a portal or round window (maybe of a ship on the bay or through a telescope), suggests European influence as well as a growing change in use of single-point perspective. The previous style of perspective used by Edo print designers was a tilted plane approach, which tilted the ground so that objects farther away were placed higher up in the scene to indicate their distance. With increased trade and influence from the west, artists began adopting some of the perspectives found in western art which can be easily seen here from the bridge lines drawing down to one point, indicating the depth of the scene.

Image Copyright, The Trustees of The British Museum

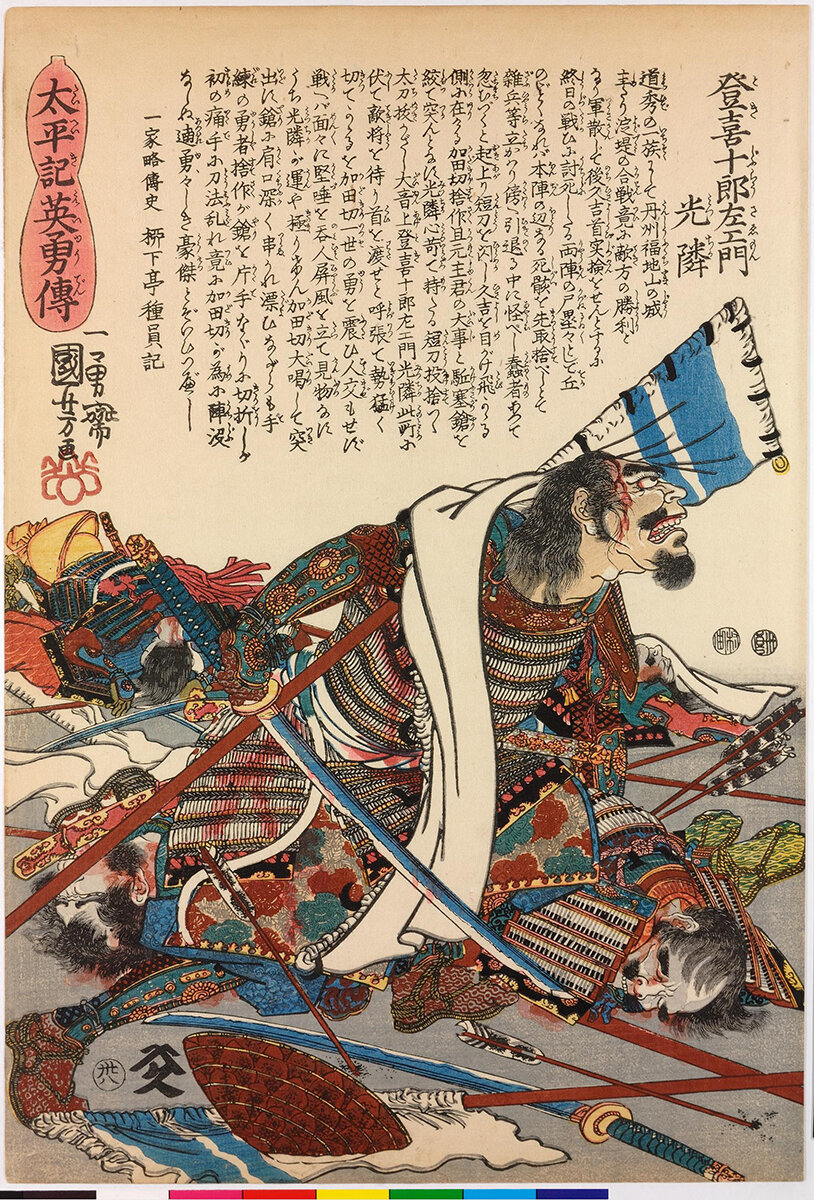

9. Toki Jūrōzaemon Mitsuchika

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, from the series Heroes of the Great Peace, c. 1848-1850, ōban.

Warrior prints make up the third largest section of Ukiyo-e designs. Although potentially less popular now due to their aggressive, slightly complicated and hectic aesthetic, warrior prints can be the most subtle, political and imbued with deeper meaning of any category. Through the ban on illicit images, japan of the 18th century was also subjected to political bans on imagery, mainly of war histories which glorified uprising, criticized the current regime, or even mentioned the great unifier of japan Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536-98). Due to these histories of both japan and china being so wildly popular, artists devised incredibly creative manners to portray and allude the imagery ban such as placing histories much further back in time, as well as using animal imagery to replace real characters in the stories (common in sexually explicit designs as well, see above “The Fisherman’s Wife”). This dramatic scene depicts a warrior crawling through his slain comrades to complete the attempted assassination of Hideyoshi; Kuniyoshi was able to create this print by changing names and adjusting the time periods.

Image Copyright, The Trustees of The British Museum

10. View of Maruyama in Nagasaki

Utagawa Hiroshige II, from the series One hundred views of famous places in the various provinces, 1859, ōban.

This final print portrays many of the classic elements of Edo Ukiyo-e print making. Here, two women (likely sex workers) are positioned in the foreground with classical, patterned robes and elaborate hair and makeup. The background lies far away and is positioned higher up (older use of traditional tiled plane perspective) while the foreground contains the main image. However, some western influence in single point perspective can be seen here in the shapes of the building and the sloping lines of the roof and porch toward the right. Many westerns hold this type of image in their mind still of classical japan because of the popularity, distribution and influence of Ukiyo-e prints like this one to the western world.

Image Copyright, The Trustees of The British Museum

A truly fascinating artistic age, Edo of the 18th and 19th centuries was a veritable wellspring of Ukiyo-e artists, designers, printmakers and art lovers. When thinking of the world’s renaissances, it is certainly appropriate and crucial to include this beautiful age of artistic production which gave society so much color, uniqueness and vibrant portrayals of life in old Japan.